“I declare the first gathering of The Foreign Lands’ Explorers open,” said Jack and everyone clapped and cheered. “The topic for today is ‘the work’.”

“’El trabajo’, in Spanish; ‘il lavoro’, in Italian; ‘o trabalho’, in Portuguese,” said Leo.

“’Le travail’, in French”, said Elizabeth.

“’Die Arbeit’, in German”, said Michael.

“’Arbejdet’, in Danish; ‘arbeidet’, in Norwegian; ‘arbetet’, in Swedish”, said Sophia.

“’Trabajo’, ‘trabalho’, and ‘travail’ come from Latin. The original word, at the time, was related to a torture instrument with three stakes. I have no idea how it progressed, but we can assume that there was a connection made somewhere by common people between ‘work’ and ‘torture’…”, explained Leo. “The Italian word comes from the Latin word ‘labor’, which was the official and standard word for ‘work’ at the time. In Spanish, French, and Portuguese a similar word also exists with a similar meaning, but usually is used in handcraft work or in the farming context. It makes sense because at the time most of the work was related with agriculture. In English, we can also see this word being used in some contexts, like in ‘labour market’.”

“Actually, there is a similar situation in German. The word ‘Werk’ also means work in a more formal manner, but it is mostly related with factories and the like. Both words ‘Werk’ and ‘work’ have the same origin. In English language the word ‘labour’ can be used, but it’s more commonly used in the farming context”, added Michael.

“Then, there is ‘job’, which can mean a task or an employment”, said Jack.

“In Spanish and in Portuguese the word is the same, but there is also the word ‘empleo’ and ‘emprego’, respectively, for ‘employment’, which is similar to English”, informed Leo.

“Yes, ‘employment’ was adopted to English via French, whose word is ‘emploi’. In French slang you can also say ‘boulot’”, added Elizabeth.

“Ok, what about ‘unemployment’? In Swedish is ‘arbetslöshet’, in Danish is ‘arbejdsløshed’, and in Norwegian is ‘arbeidsledighet’”, said Sophia. “Basically it means ‘without work’”.

“In German is not so different: ‘Arbeitslosigkeit’”, added Michael.

“In French is ‘chômage’”, said Elizabeth.

“’Chômage’?! Where that came from?”, asked Jack.

“It comes from the Latin word ‘caumare’, which means to take a break during the heat”, explained Elizabeth.

“That doesn’t seem to make much sense…”, laughed Sophia.

“Well, try working during the heat and you’ll probably start to see some sense…”, commented Jack. “We all have to learn the ropes with those who came before us.”

“Learn the ropes? What do you mean?”, asked Leo.

“It’s an idiomatic expression that means learning to do a job”, answered Jack. “It was used when new sailors had to learn how to tide the ropes in sailing boats.”

“As they say in Germany: ‘die Arbeit, die uns freut, wird zum Vergnügen’. This means ‘the work that we enjoy becomes pleasure’”, said Michael.

“Unless you ‘tombes dans le panneau’”, said Elizabeth. As everyone stared at her, she explained: “You can fall into a trap”. Then everyone went “Ahhhh”.

“You can always take a ‘föräldrapenning’, as the Swedish say. Or ‘foreldrepenger’, in Norwergian. Or ‘forældreorlov’ in Danish”, said Sophia.

“What exactly is that?”, asked Leo.

“Parental leave”, clarified Sophia.

“Oh, ‘congé parental’, in French”, said Elizabeth.

“’Permiso parental’ in Spanish; ‘congedo parentale’, in Italian; and ‘licença parental’, in Portuguese”, said Leo.

“’Elternurlaub’, in German”, said Michael.

“Well, you would have to have a child first…”, commented Elizabeth.

“I declare the first gathering of The Foreign Lands’ Explorers open,” said Jack and everyone clapped and cheered. “The topic for today is ‘the work’.”

“’El trabajo’, in Spanish; ‘il lavoro’, in Italian; ‘o trabalho’, in Portuguese,” said Leo.

“’Le travail’, in French”, said Elizabeth.

“’Die Arbeit’, in German”, said Michael.

“’Arbejdet’, in Danish; ‘arbeidet’, in Norwegian; ‘arbetet’, in Swedish”, said Sophia.

“’Trabajo’, ‘trabalho’, and ‘travail’ come from Latin. The original word, at the time, was related to a torture instrument with three stakes. I have no idea how it progressed, but we can assume that there a connection was made somewhere on the way by common people between ‘work’ and ‘torture’…”, explained Leo. “The Italian word comes from the Latin word ‘labor’, which was the official and standard word for ‘work’ at the time. In Spanish, French, and Portuguese a similar word also exists with a similar meaning, but usually is used in handcraft work or in the farming context. It makes sense because at the time most of the work was related to agriculture. In English, we can also see this word being used in some contexts, like in ‘labour market’.”

“Actually, there is a similar situation in German. The word ‘Werk’ also means work in a more formal manner, but it is mostly related with factories and the like. Both words ‘Werk’ and ‘work’ have the same origin. In the English language, the word ‘labour’ can be used, but it’s more commonly used in the farming context”, added Michael.

“Then, there is ‘job’, which can mean a task or an employment”, said Jack.

“In Spanish and in Portuguese the word is the same, but there is also the word ‘empleo’ and ‘emprego’, respectively, for ‘employment’, which is similar to English”, informed Leo.

“Yes, ‘employment’ was adopted to English via French, whose word is ‘emploi’. In French slang, you can also say ‘boulot’”, added Elizabeth.

“Ok, what about ‘unemployment’? In Swedish is ‘arbetslöshet’, in Danish is ‘arbejdsløshed’, and in Norwegian is ‘arbeidsledighet’”, said Sophia. “Basically, it means ‘without work’”.

“In German is not so different: ‘Arbeitslosigkeit’”, added Michael.

“In French it is ‘chômage’”, said Elizabeth.

“’Chômage’?! Where did that come from?”, asked Jack.

“It comes from the Latin word ‘caumare’, which means to take a break during the heat”, explained Elizabeth.

“That doesn’t seem to make much sense…”, laughed Sophia.

“Well, try working during the heat and you’ll probably start to see some sense…”, commented Jack. “We all have to learn the ropes with those who came before us.”

“Learn the ropes? What do you mean?”, asked Leo.

“It’s an idiomatic expression that means learning to do a job”, answered Jack. “It was used when new sailors had to learn how to tide the ropes in sailing boats.”

“As they say in Germany: ‘die Arbeit, die uns freut, wird zum Vergnügen’. This means ‘the work that we enjoy becomes pleasure’”, said Michael.

“Unless you ‘tombes dans le panneau’”, said Elizabeth. As everyone stared at her, she explained: “You can fall into a trap”. Then everyone went “Ahhhh”.

“You can always take a ‘föräldrapenning’, as the Swedish say. Or ‘foreldrepenger’, in Norwegian. Or ‘forældreorlov’ in Danish”, said Sophia.

“What exactly is that?”, asked Leo.

“Parental leave”, clarified Sophia.

“Oh, ‘congé parental’, in French”, said Elizabeth.

“’Permiso parental’ in Spanish; ‘congedo parentale’, in Italian; and ‘licença parental’, in Portuguese”, said Leo.

“’Elternurlaub’, in German”, said Michael.

“Well, you would have to have a child first…”, commented Elizabeth.

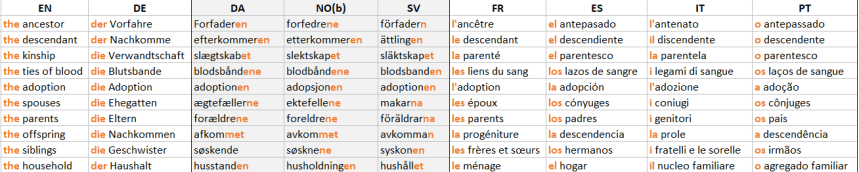

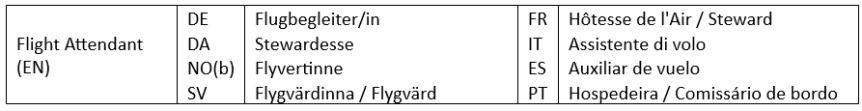

After this introduction to the topic, they decided to compare the name of some professions in different languages. They started with the firefighters.

While in the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic languages the focus is on fire (they are the people of the fire / those who fight the fire), in Latin languages the focus is on the pumps that were used at the beginning of firefighting (they are the people of the pumps).

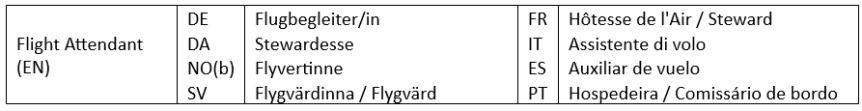

Between ‘assistant’ and ‘host’ / ‘hostess’ or ‘steward’ / ‘stewardess’, there is not much difference.

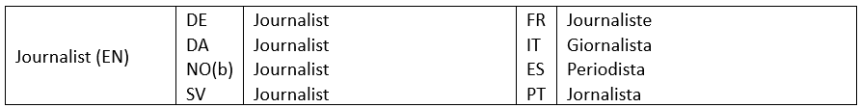

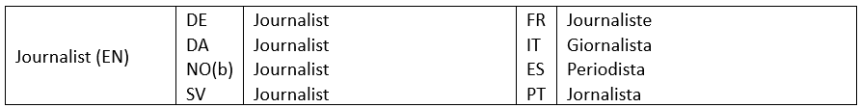

In this case, except in the Spanish language, the expression is very similar to all other languages. “Journalism” was a term born in the 18th century in France and comes from “jour”, as in “report every day”. In Spanish, “newspaper” is “periódico”, hence the “periodista”.

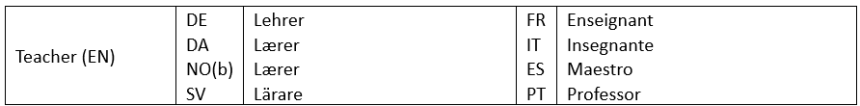

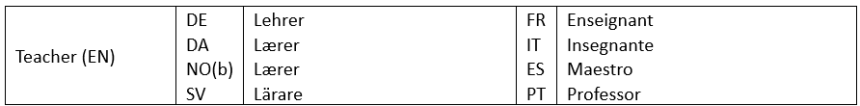

In German and in the Nordic languages, the word refers to an instructor, someone who provides training for someone to acquire a skill, which has a similar meaning for “teacher”, although the root is different. The perspective is “to show how it’s done”. In Latin languages, the perspective is “someone who dominates an art and transmits its knowledge to their disciples”. In these languages, the teacher is regarded as a kind of “keeper of knowledge”. This is even more emphasised in Spanish, where the teacher is considered a “master”. Actually, in the other Latin countries, a teacher used to be called “master” and in some contexts it is still the case.

As it was getting late, they decided to wrap up. They could discuss and compare terms in different languages for hours, but they all had classes the next morning. However, when everyone was preparing to leave, Leo remembered something.

“Do you know the origin of the word ‘salary’?”

Everyone looked at Leo.

“Salt was extremely important during the Roman Empire. So, it was the reference to pay soldiers what was due to them. It was the ‘salt portion’ they could have. They still use that term in English, in Portuguese (‘salário’), in French (‘salaire’), and in Spanish in certain contexts (‘salario’).”

“If it’s a constant pay, for example every month, it’s ‘sueldo’. If it is an irregular pay it’s a ‘salario’”, said Elizabeth.

“Exactly”, confirmed Leo. “It’s similar in Italian: ‘salario’ is an hourly pay whereas ‘stipendio’ is a fixed pay”.

“That’s also similar in German. If it’s fixed it’s ‘Gehalt’ and if it’s variable it’s ‘Lohn’”, said Michael.

“Ah, in Swedish it’s ‘lön’, in Danish it’s ‘løn’, and in Norwegian it’s ‘lønn’”, added Sophia.

And, on that note, they reluctantly went back home.

![]()

![]()

![]()