If you look for films, TV series, or books with “wife” as a keyword, you will have a lot to choose from. There are titles for all tastes. Whatever the title is, it is clear what “wife” means: a woman who has acquired a new social status after marrying. Such a woman can also be called “spouse”, although “wife” is most widely used.

So, a married woman is a wife. This “transformation” does not happen in other languages. For example, in German, a married woman is still a woman (frau). The same is true for Latin-based languages: femme (in French); moglie (in Italian); mujer (in Spanish); mulher (in Portuguese). In these languages, “wives” can also be called “spouses” in more formal contexts: épouse (in French); sposa (in Italian); esposa (in Spanish); esposa (in Portuguese). “Spouse”, and its direct translations, come from the Latin spondeo / sponsus, meaning “a promise to marry”. This word is valid both for women and men, with the appropriate masculine/feminine change.

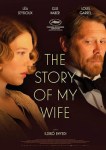

In some film/tv series/book titles, the translation is quite straightforward. For example, “The Story of My Wife” can be translated as: “Die Geschichte meiner Frau” (in German); “L’histoire de ma femme” (in French); “Storia di mia moglie” (in Italian); “La historia de mi mujer” (in Spanish); “A História da Minha Mulher” (in Portuguese).

In some film/tv series/book titles, the translation is quite straightforward. For example, “The Story of My Wife” can be translated as: “Die Geschichte meiner Frau” (in German); “L’histoire de ma femme” (in French); “Storia di mia moglie” (in Italian); “La historia de mi mujer” (in Spanish); “A História da Minha Mulher” (in Portuguese).

But things can get complicated very fast… For example, how to translate “The Good Wife”? If you translate “wife” to its usual translation as “woman”, “The Good Woman” can be either married or single. However, in this case, the fact that she is married is essential for the story. Therefore, the title has to reflect her social status. One option is to maintain the title in English and not translate it at all, which was what countries like Ecuador, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, and Sapin did. Another option is to change the title in some way:

But things can get complicated very fast… For example, how to translate “The Good Wife”? If you translate “wife” to its usual translation as “woman”, “The Good Woman” can be either married or single. However, in this case, the fact that she is married is essential for the story. Therefore, the title has to reflect her social status. One option is to maintain the title in English and not translate it at all, which was what countries like Ecuador, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, and Sapin did. Another option is to change the title in some way:

- In Brazil, they opted for a mix title: “The Good Wife: Pelo Direito de Recomeçar” [The Good Wife: For the Right to Start Over Again”].

- In French Canada, they changed the title slightly: “Une femme exemplaire” [An exemplary wife/woman], which is very similar to the original title.

- A similar option was used in Uruguay, but using the other possible word for “wife” (“spouse”): “La esposa ejemplar” [The exemplary spouse].

Changing the title entirely is another option, which was what they chose to do, for example, in the title “The Time Traveler’s Wife”. In many countries, this film was translated as “I will always love you”, focusing on time and not on the wife. This is interesting. There are many English titles like this: “The Zookeeper’s Wife”, “The Preacher’s Wife”, “The Bishop’s Wife”, “The Serial Killer’s Wife”, “The Astronaut’s Wife”, among others. Yet, in non-English speaking countries, the tendency is to choose a different title, more tuned with the story itself and not focused on the wife and whom she is married to.

Changing the title entirely is another option, which was what they chose to do, for example, in the title “The Time Traveler’s Wife”. In many countries, this film was translated as “I will always love you”, focusing on time and not on the wife. This is interesting. There are many English titles like this: “The Zookeeper’s Wife”, “The Preacher’s Wife”, “The Bishop’s Wife”, “The Serial Killer’s Wife”, “The Astronaut’s Wife”, among others. Yet, in non-English speaking countries, the tendency is to choose a different title, more tuned with the story itself and not focused on the wife and whom she is married to.

“Wife” and “woman” have the same origin: Old English wif, meaning “human female”. “Wife” is connected to an expression meaning “a woman in a legal relationship” while “woman” is like a kind of “female man”. Nordic languages follow the same logic and they have the same distant origin, but have evolved differently. In French, “femme” comes from the Latin femina, meaning female, and, in the other Latin-based languages, the word originates from the Latin word mulier, meaning “woman”, especially “married woman”. “Frau” follows exactly the same logic. In Italy, “wife” can also be called “donna”, which comes from the Latin word domus, meaning “house”. Therefore, “donna” is the “mistress of the house” (her house as a married woman).

Therefore, in reality, a “woman” is a “married woman”. Unmarried women are usually called “girls”, assuming that only young women are unmarried. This is valid for the other languages here analysed. This situation is reflected in women’s titles in society: if single, they are called Miss, Fräulein, Mademoiselle, Signorina, Señorita, Menina; and if married they are called Mrs, Frau, Madam, Signora, Señora, Senhora.

We can see that the words to designate women are rooted in the patriarchal system: their destiny was to get married and take care of their home and children. Therefore, they had two statuses: girls (as children, thus, unmarried) or women/wives (married). Unmarried women were unheard of or did not make sense. Or they were witches. Or spinsters, who were not well regarded in society. Or they would become nuns. Or, at the beginning of the 20th century, they were considered hysterical and locked up in madhouses.

Nowadays, more and more women are choosing not to get married and actually having a professional career. There are those who do not marry and just get together. Therefore, the concept of “woman” in all these languages is changing. It is not equivalent to “married woman” any more and women are becoming persons by themselves, not existing as a “wife/woman” of a man. Maybe new words were needed, but we have to work with what we have…

Sources:

- Spouse (Etymonline)

- Film: “The Story of My Wife”

- TV Series: “The Good Wife”

- Film: “The Time Traveler’s Wife”

- Wife (Etymonline)

- Woman (Etymonline)

- As muitas faces (linguísticas) da mulher

- Frau (Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen)

- Donna (Etymonline)

- Scientif Article: “Maritus/marita: Notes on the Dialectal Variation in Relation to Lexical Choices”, by Catarina Gaspar

This article is part of the BRINGING ACROSS series

“Translation” in different languages comes or is based on the meaning of two similar Latin words which convey the idea of transferring something from A to B… “bringing across”. Every month, a translation challenge is presented according to a keyword.